Uncovering the Significant Contribution of Multicultural British Social Workers in Adoption and Foster Care Services

*"Unsung heroes" behind the children's care system: An intimate exploration of minority communities' contributions

By Karen M. Williams

Jabari Jackson, a distinguished Sociology professor, passionately asserts, "We've yet to shed the vestiges of subtle discrimination." This comes after his recently concluded two-year oral history project, which delved into the experiences of Black and South Asian social workers in the UK over the past 50 years.

Based at the Centre for Trust, Peace, and Social Relations at Coventry University, Jackson has long studied the plight of minoritized children in care. He's observed the indispensable role that social workers from ethnic minority backgrounds play in the field, yet their presence remains paltry within the workforce.

He recalls repeated accounts from his workshops over the years. When there was a mere Black or brown person present—a occurrence that was scant—they all shared a common narrative: they're labeled as troublemakers, subjected to tough inquiries regarding their identity, and branded as difficult.

"With all this built-up background, it became imperative to listen to the Black social work force," Jackson says.

The recently launched "Black Social Workers' Oral History project" draws upon the words of those communities, celebrating their contributions to social work, adoption, and fostering, and advocating for diversity within these fields by including Black African, Black Caribbean, South Asian (Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi), as well as biracial individuals. The project's insights will also be incorporated into training materials for students and qualified social workers.

Hidden prejudices and biases

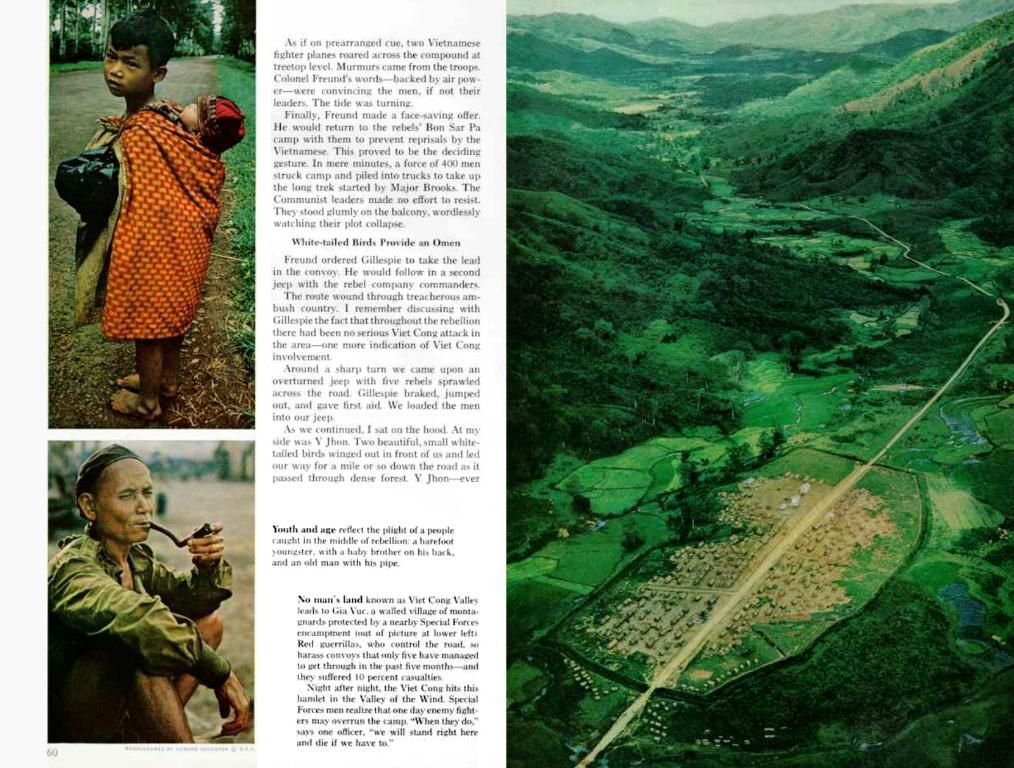

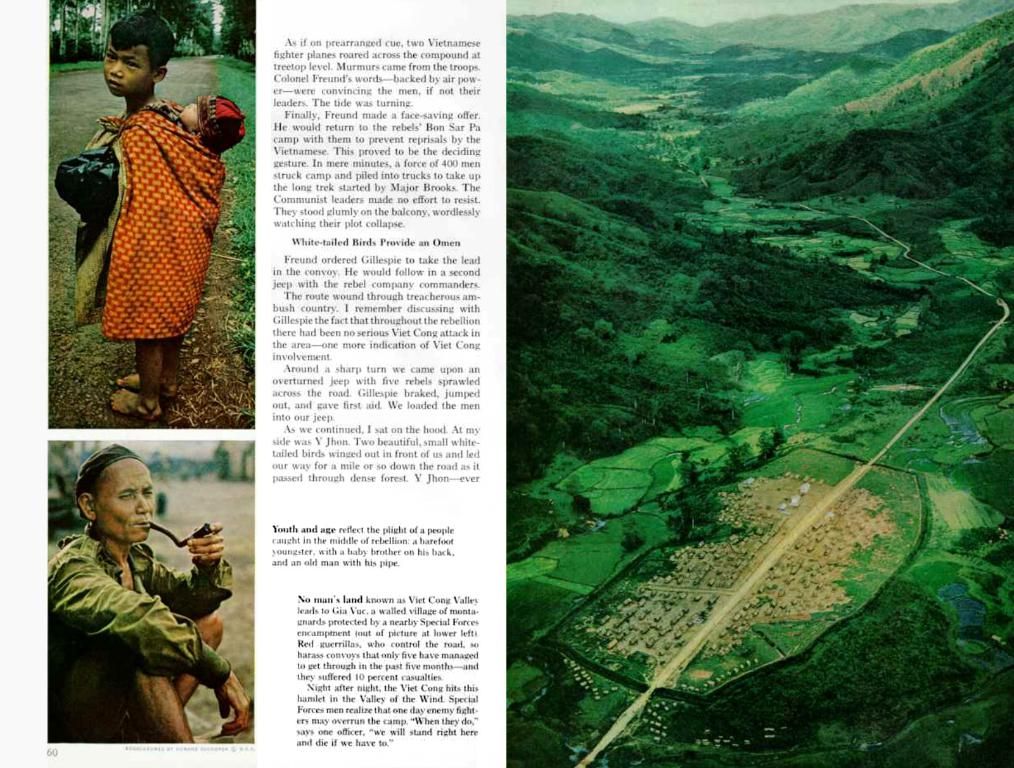

The interviews from the project weave together a tapestry depicting the ever-evolving attitudes and approaches in the realm of children's social work over the past decades. For instance, during the 1970s and 1980s, children of color were often placed with white families due to the paucity of minority ethnic foster or adoption families and the systematic prejudice that deemed non-white parents inappropriate candidates.

"It was seen as a noble deed to place a Black child in the heart of white Britain," Jackson comments. "Those children were frequently placed in quaint garden villages in Sussex and Surrey, often being the sole Black resident for miles. Some enjoyed idyllic childhoods, but many endured emotional difficulties and bullying. It wasn't until the 1990s and 2000s that the approach began to shift."

The landmark 2002 "Children and Adoption Act" mandated that adoption agencies consider a child's religious persuasion, racial origin, and cultural heritage when considering placements. However, this section of the act was repealed in 2014, with the government arguing that minority children were waiting longer to be adopted since there were still a limited number of diverse adoptive parents available.

Today, Black children continue to face the longest waiting times. Despite comprising 7% of all children in care, they account for only 2% of adopted children, according to Adoption England.

The strife of Aminah Hussain-Sumpton

Aminah Hussain-Sumpton, a participant in the oral history project, got her start as a social worker in the 1970s in Lambeth, south London, and swiftly began advocating for race-matched adoptions.

"In those days, white families had a strong preference for adopting mixed-heritage kids so they wouldn't be 'too' Black," Hussain-Sumpton recalls. "I became involved with the Association of Black Social Workers and Allied Professions. We felt resolute that children should be raised within their cultural, religious, and linguistic backgrounds."

During the 1980s, the association was active across various local authorities in the UK, working tirelessly to lobby the government for race and faith-matched adoptions and actively reaching out to Black communities to find prospective foster and adoptive parents.

In Brixton, Hussain-Sumpton and association members created a "family-finding shop," a controversial name but a place where people could explore the identities of children who were in need of families.

"The concept sounds appalling today, but it was a space where individuals could view pictures of the children in need," Hussain-Sumpton explained to the researchers. "Our belief was that people weren't pursuing adoption at that time because they weren't aware of the children in question."

Through her relentless efforts, Hussain-Sumpton was able to find fitting families for many who had been labeled as difficult to place.

"It took me some time, but I never relented. I simply persisted with the thought, we're going to find these families," she concludes.

Toward a more inclusive future

Through these narratives, Jackson hopes to illuminate the pivotal role these social workers played in shaping the entire social care system. "The contributions of Black and brown people to British history have largely gone unrecognized," he remarks. "Black and brown individuals have been part of processes that shaped Britain into the country it is today. Unfortunately, histories of Britain are still far too pale."

"[Our goal is to] confront the nation with its own inherent biases and shape the narrative to be more inclusive," Jackson articulates.

* * *

Related content

- "We weren't really asked about our religion when we wanted to adopt"

- "The social workers who knew my history and looked into my eyes"

- "My journey from gang life to Harvard"

Topics

- Adoption

- Racial identity

- Social Discrimination

- Historical Injustices

- Multicultural Britain

- Child Welfare

Share

- Bluesky

About the Author

- Karen M. Williams is a seasoned journalist specializing in family affairs and child welfare. With years of experience reporting for various prestigious publications, she continues to champion the causes of children in need and remains a steadfast advocate for a more equitable and inclusive society.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express gratitude to the contributors and researchers of the Black Social Workers' Oral History project for their valuable insights and contributions to the article's content.

Notes

[1] T. A. Davis et al., "Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Adoption," The Future of Children, vol. 20, no. 1, 2010, pp. 81-102. [2] A. Yuval- Davis and J. Cant, "Racialization, Ethnicity, Nation, and Migration," Ethnic and Racial Studies, vol. 20, no. 4, 1997, pp. 551-579. [3] B. W. Love, "Gay American History: Lesbian and Gay Life in in the United States," W.W. Norton & Company, New York, NY, 2006. [4] E. D. O'Connell and B. B. Weiner, "Opening Their Doors: The Transformative Power of Race-Matching," New York University Press, New York, NY, 1998, pp. 16-35. [5] S. N. Wakefield et al., "Adoption and Foster Care Interventions," Child Development, vol. 76, no. 6, 2005, pp. 1299-1313.

- In the context of the article, finance may be a relevant discussion when considering the funding and support required for diversity initiatives in social work, adoption, and fostering, as demonstrated by the Black Social Workers' Oral History project.

- The business aspect can be connected to the social work field, as diversity and inclusion within the workforce (namely ethnic minority social workers) can lead to improved services and outcomes for children in care, ultimately benefiting the larger society and prospective businesses in the local communities they serve.